Music rights and permissions are complicated, and I’m no expert, but I put together a quick rundown of what I know about music rights for my own use, and maybe it’ll be useful to someone else so here it is. If you’re working on a project that needs music, this should help clarify what kind of rights you’ll have to deal with to keep everything on the up-and-up.

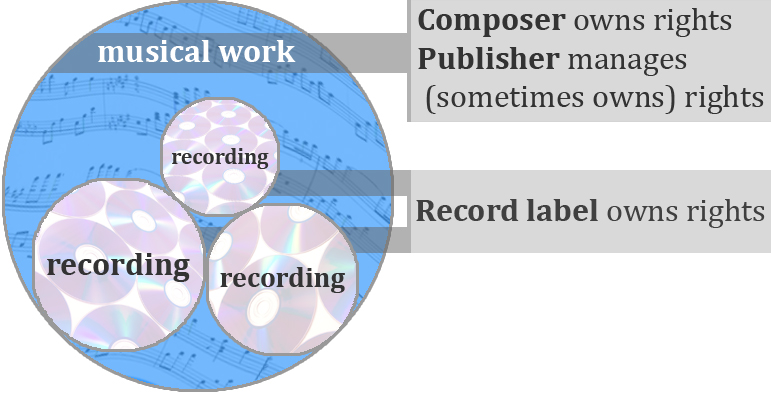

First of all, there are a few things you need to understand about the components of a piece of music and the different entities involved in the process of making music. Every song you hear on the radio, on a CD or in your digital library is made up of two parts: the musical work and the recording.

- The musical work is defined as the notes and (often) lyrics of the song, usually written down on a page as a score or sheet music. This is the essence of the song as created by the composer or writer, and he or she owns the copyright to the musical work. When a composer signs with a music publisher, the publisher often takes care of managing the copyright for the composer.

- The recording is the, well, recording. Someone recorded artists playing and singing the notes and lyrics of the musical work, then imprinted that on a CD or created a digital code of that recording. The record label who paid for this recording and imprinting owns the rights to the recording.

- Note that all recordings include the musical work, but the musical work can exist without any recordings. This is why anyone who wants to make a recording of a song must get permission from the person who wrote the song (unless the song is now out of copyright).

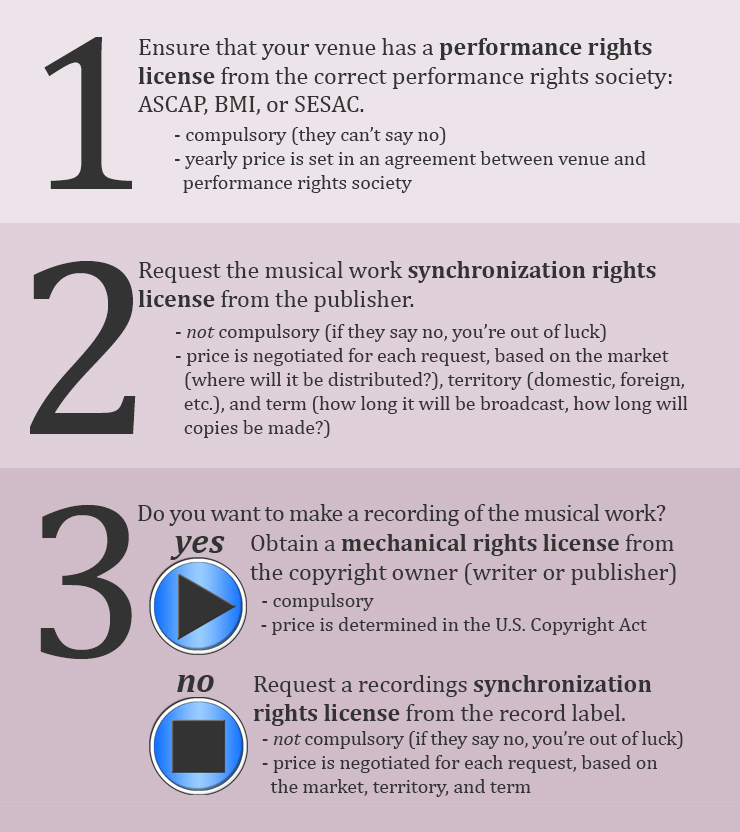

Next, we can go through the three main steps to be sure you’ve got all your ducks in a row. There are three kinds of rights involved in using a musical work or recording; the details of what you want to do will decide which of the rights you need to acquire and from whom.

- Venue: it sounds weird, but every project has a venue. It’s wherever your project will be seen or shown to others–a movie theater, a classroom, a website. You probably don’t have to worry about this, really, most venues will have this buttoned down. But this is why some videos on YouTube are allowed to have copyrighted music while others are stripped–YouTube is the venue, and they’ve worked out an agreement with the performance rights societies about how many and which copyrighted songs can be ‘performed’ on YouTube.

- Performance rights society: each society has a handy online look-up tool (ASCAP, BMI, SESAC) to help you find info about songs and specific recordings. It’s a tedious process, because these searches don’t let you filter or search by more than one variable. And there is no consistency in how writers’ and artists’ names are entered (for instance, I’ve found “Monroe Bill,” “Monroe B” and “Monroe William” all pointing to the same writer/artist). So, if it’s a popular song, you’ll need to read through a bunch of page results to make sure you find the correct version of the song–try to match up the writer and artist.

- Composer/writer: if you have the song in your possession, the liner notes or “Get Info” in iTunes will tell you who wrote it. If not, you can do a Google search–but make sure you check a couple of sources to validate whatever info you find.

- Publisher: coincidentally, the info you’ll get from the performance rights society result will include publisher info. Two birds!

- Record label: a quick way to find this, if you don’t have the liner notes or it’s not in the digital information, is to search for the album on Amazon–each entry includes record label and the year it was released.

Once you’ve figured out which license(s) you’ll need and from whom–look for the links to ‘licensing’ on the websites of the music publisher or record label, or someone to contact. There will be forms for you to fill out to request your license. For example, on the Warner/Chappell Music site there’s a whole section with licensing resources. FYI, a synchronization license will look something like this.

Let me know if you see anything that needs to be corrected. There are lots of resources out there if you want to learn more, try the books Media Law for Producers and Clearance and Copyright: Everything you need to know for film and television. Also media lawyers. Lawyers are reliable.